So, who was Lella Lombardi? (and why is it so difficult to find out about her?)

Since the inauguration of the F1 World Championship for Drivers in 1950, nearly 900 drivers have attempted to qualify for the starting grid. Only 5 of these have been women, just 2 of whom have managed it. With 17 entries and 12 starts, by far the most successful of these women is Lella Lombardi. For many who know of her only through motor sport trivia books or quizzes, she is “the only woman to have finished an F1 Grand Prix in a points-scoring position”, but this record – remarkable as it is -does her a disservice, as it overshadows the rest of her 23-year career.

I first became aware of Lella in 1974, thanks to a double-page advert in Autosport magazine devoted to the woman who was about to attempt to qualify for the British Grand Prix. Further investigation revealed that she was giving a good account of herself in F5000 that year, earning her stripes in the big, unwieldy single-seaters. She remained on my radar sporadically after her brief F1 career ended, although many contemporary magazines gave few column inches to her exploits in other categories.

When I read of her passing in 1992, at the tragically young age of 50, I learned from her obituaries that she had been Italian national F.850 champion in 1970; winner of the Ford Escort Mexico Kleber Challenge title in 1973; had shared the highest-placed finish post-war by an-all female crew in the Le Mans 24-Hours (with Christine Beckers in 1977). I already knew that she had claimed three outright victories in the World Sports Car Championship, which she’d followed up with numerous class wins in the European Touring Car Championship and the 1985 Division 2 ETCC Crown (with Rinaldo Drovandi). This seemed a pretty impressive record for any driver, but despite that, and Lella’s significance to the sport for gender-obsessed F1 statisticians, it baffled me for years to follow as to why there had never been a biography written about her, not even in her native Italy.

After a later-life epiphany as a motor sport writer, when BHP Publishing offered me the opportunity to write about “whomever I wanted”, I jumped at the chance to produce her biography. Very quickly, it became apparent why nobody had attempted it before. Lella gave very few interviews during her lifetime and largely kept herself to herself. Her career spanned the years 1965 to 1988, and for a devout Roman Catholic from a then very traditional Italy, the fact that she was also gay meant that she built a defensive wall around her personal life. This was to protect her partner Fiorenza, who was a constant presence alongside her from the very earliest days of her career, and helped her acquire her first racing car in 1965, an F.875 CRM, to learn her craft in the new “Formula Monza” that was launched that year. Lella’s guarding of their life together was so effective that many of the Italian journalists who knew the couple well enough to be invited for dinner at their home, never knew Fiorenza’s surname.

The daughter of a butcher from the tiny village of Frugarolo, near Alessandria Lella was a natural athlete and became a capable handball player. She helped her father to negotiate with traders at the wholesale meat markets, while racing her Lambretta against the village boys. A request from the local priest to tame her wild ways fell on deaf ears. She was the first person in her family to hold a driving licence, having learned at the wheel of the butcher’s van, and there are several hair-raising stories of her adventures making deliveries along the Ligurian peninsula.

Most photos of Lella show her in either racing overalls or jeans and sweatshirts. It was a surprise to discover that before she became a racer, she was a very accomplished jive dancer; she and her childhood friend Giuseppe Bonadeo won many local and regional dance contests. Discovering a photo of her in a party dress was almost disconcerting! It was also interesting to learn that her favourite pastime when she was not racing was fishing.

Her friends reflect on the fact that – outside her local territory – the Italian mass media gave little space to Lella’s exploits, and she seems to have received much greater press attention in both the UK and Australia, where she was very popular after two exceptional F5000 outings. What is equally clear, however, is that despite her talent and tenacity as a racer and the quality of her technical feedback, Lella’s career during the 1960s and 1970s was hamstrung by a combination of misogyny and inattention from some team owners. In one of her rare interviews, she told how she hated the condescending smiles from some male rivals at the start of her career, with the patronising suggestion, “I’ll help you because you’re just a woman who won’t be able to do this alone.” Other than that, she rarely complained about the way she was treated by her male rivals.

When she eventually reached F1, in mid-1975, she was soon frustrated with her March’s perpetually inconsistent handling which showed no improvement regardless of any set-up changes, A well-documented story recounts that the reason for her car’s mysterious handling only came to light when her successor at March, Ronnie Peterson, reported the same issue when he was given Lella’s former chassis to drive in 1976. When the tub was stripped down at the factory, a cracked internal bulkhead was found, by which time the damage to Lella’s F1 reputation had been done. March boss Robin Herd later admitted, ‘It was one of the few times that she complained about the inequality of F1 – because nobody had listened to her about the problem with the car.’

Gender was something that never concerned her; after her F1 debut in 1975, she told a local reporter, “I hope that, now, people have begun to understand that Lella Lombardi is a racer who is a woman, rather than a woman who races. That is a distinction that I care about very much.’ Later that year, in Autosprint, she claimed, ‘I have never considered the male-female issue, only the competition that exists between different drivers. Under the helmet, women and men are completely equal.’

One of the recurring themes from the hundred-plus interviews I conducted whilst researching Lella’s story is that nobody had a bad word to say about her. This is especially unusual in the dog-eat-dog world of professional motorsport where feelings and opinions are amplified by rivalry. She was a quiet force of nature, tenaciously determined to follow her passion for racing above all else, even in this meant making great personal sacrifices with limited financial resources. Her technical ability is often mentioned and her excellent mechanical sympathy was appreciated by her prototype and touring car co-drivers. She was quick, too, as evidenced by seventeen career pole positions and twenty fastest laps.

The ups and downs of Lella’s career, with all its attendant challenges and setbacks, read like a Hollywood film script, but it’s one that also has a tragic ending. Having recently formed her own team, Lella Lombardi Autosport, ill-health forced her to retire from racing early in 1988. The pain she thought was due to a sailing injury incurred three years previously turned out to be breast cancer, and she passed away peacefully in Milan’s San Camillo Clinic in March 1992, three weeks before her 51st birthday. I am tremendously grateful to the many friends, family members, former colleagues and rivals, and – particularly – to Lella’s niece Patrizia for their help and support in creating a properly three-dimensional image of this remarkable racer.

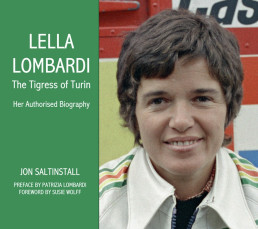

“Lella Lombardi: The Tigress of Turin, Her Authorised Biography” by Jon Saltinstall will be published by BHP Publishing in August 2025.

© Jon Saltinstall, 2025.